Nonstimulus arithmetic

Why the American Rescue Plan has to be big

Back in January 2009 I posted an entry to my blog titled “Stimulus arithmetic” that worked through the math of the looming output gap and what we knew about the Obama stimulus. I warned that the stimulus was drastically underpowered, and issued a dire political warning that unfortunately came true:

“I see the following scenario: a weak stimulus plan, perhaps even weaker than what we’re talking about now, is crafted to win those extra GOP votes. The plan limits the rise in unemployment, but things are still pretty bad, with the rate peaking at something like 9 percent and coming down only slowly. And then Mitch McConnell says “See, government spending doesn’t work.””

What I want to do here is something roughly analogous for Joe Biden’s American Rescue Plan. However, I say “roughly analogous” advisedly. As I and others keep trying to get across, mainly in vain, the output-gap-versus-stimulus framework really doesn’t apply to the current crisis, and misuse of that framework can lead you badly astray.

So what I’m going to do here is try to answer three questions:

1. How should we think about the crisis and the appropriate response?

2. Why is the Biden plan so big?

3. Is it too big, and what are the risks from its size?

The logic of nonstimulus

We are not in a conventional recession — a decline in output due to insufficient aggregate demand. What we’re suffering from, instead, is a partial lockdown, the result of both public policy and private choices, that has sharply curtailed high-infection-risk activities, like indoor dining.

Pumping up overall spending with fiscal and monetary policy wouldn’t send diners back into restaurants, nor should it. So we aren’t experiencing a normal output gap, something that should be closed by stimulus. It’s actually not clear whether we even want employment and GDP to be higher before vaccination gives us herd immunity.

What, then, is the role of policy? As some of us have been arguing all along, it’s not stimulus, it’s disaster relief: an attempt to shore up the living standards of those hurt by the temporary lockdown, as well as providing resources to deal with the pandemic itself. Or as I recently argued, you can think of what we’re doing as being something like fighting a war — special expenditure in the face of an emergency.

And when you’re fighting a war, you don’t decide how much to spend by asking how much stimulus you need to close an output gap; you ask how much you need to spend to achieve victory.

That said, the appropriate size of the relief package is related to, though not fully determined by, the fall in incomes caused by the pandemic.

As I just explained, standard concepts of the output gap, like those published by CBO, don’t make much sense in the current situation. And CBO’s estimates — which show a U.S. economy operating significantly above capacity in 2019 — are questionable on their own terms too. But standard potential output measures do provide a quick, fairly reasonable estimate of how much growth we should have had if it weren’t for the pandemic. Compare that with actual growth and it looks like this:

So as of the fourth quarter we were 4.3 percent below where we might have expected to be. That’s a shortfall — not exactly a gap — of about $950 billion at an annual rate.

So why are we talking about a relief package roughly twice that size?

Why is the package so big?

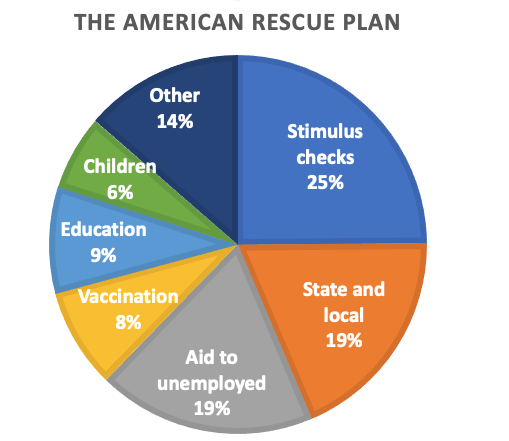

The American Rescue Plan will soon take the form of legislation, and legislation specifies spending on programs. So it’s natural to describe the plan in terms of those programs; it looks like this:

Worth noting that those checks to households, although they dominate much discussion, are only about a quarter of the plan (and might end up being less if the income limits are scaled down.)

But I think it’s helpful to think of the plan not merely in terms of specific programs but also in terms of the broader functions those programs are intended to serve. And I find myself thinking of three broad categories, which we can imperfectly map onto the details of the plan. They are

1. Pandemic control

2. Income support

3. Belt and suspenders

By pandemic control I mean spending intended to directly limit the spread of the coronavirus and hasten the end of the plague. Getting shots in arms is the most obvious element, but things like providing aid to schools so they can reopen safely is also in the same bucket. You might think that such spending would be uncontroversial — that is, you might think that if you were completely unaware of U.S. political reality. Still, it’s clearly the least controversial piece of the package. And it’s also a lot of money, several hundred billion dollars.

By income support I mean programs meant to cushion people hurt financially by the pandemic. Enhanced unemployment benefits are the prime example, but there are others. For example, a good part of aid to state and local governments is about compensating these lower levels of government for lost revenue and increased expenses associated with the pandemic

Finally, I’m suggesting “belt and suspenders” as a catchall for programs that aren’t narrowly targeted on those hurt by the pandemic, but may be worth doing because they will provide aid to those who need help but don’t qualify under more focused programs — for example, workers facing reduced hours and wages who don’t qualify for unemployment insurance. The prime example is, of course, those $1400 checks, which will go to many people who don’t need help but will also deliver help to a substantial number who do need it but aren’t getting it from other programs.

Belt and suspenders policies also happen to be very popular; wonks may not love those checks, but the general public really does. And that’s not irrelevant: in America 2021 you can’t expect to enact good policies just by making a technocratic case that they’re good, so it’s worth having some sweeteners as part of the package.

So what I would argue is that realizing that all three kinds of policy are involved helps explain why the rescue package is so big, and perhaps why it should be so big.

Income support means compensating people who have lost income to the pandemic; if the compensation were perfect, it would exactly match the decline in GDP, which is also national income (technical issues aside). Because some people fall through the cracks, it’s probably a bit less than that. But it’s fair to think of income support as being roughly equal to the decline in GDP.

This means that when you add in pandemic control, you’re going to end up with a package that’s bigger than the decline in GDP, hence bigger than conventional (if misleading) estimates of the output gap. And when you add in belt-and-suspenders, you easily end up with a package much bigger than the “output gap.”

And there’s nothing necessarily wrong with that! If you think of this as stimulus designed to boost demand, it may seem like overkill — but that’s not what it is and what it’s doing. Because it’s disaster relief that includes but goes beyond income support, it should be bigger than the income decline alone.

But the fact that a big package is justified doesn’t ensure that it poses no problems. How should we think about inflation risk?

Overheating?

The Biden plan isn’t about stimulus, but it will nonetheless be stimulating, just as wartime spending isn’t about boosting demand but nonetheless does in fact provide a demand boost. The question everyone is arguing about thanks to Larry Summers is whether the size of the proposed package will boost demand so much that it leads to economic overheating and a surge in inflation.

Here’s where I think a three-way classification helps clarify our thinking.

First, income support doesn’t seem a likely source of overheating, because it’s basically compensating for income losses, not adding fresh demand. It’s stimulus in the sense that it heads off possible Keynesian spillovers from the non-Keynesian aspects of the slump, but that’s a matter of containing a downward spiral in demand rather than adding fresh demand.

Belt-and-suspenders policies like those checks will boost demand, because for many of the recipients the checks won’t be offsetting income losses. However, the multiplier on this spending is likely to be quite low, because people who didn’t need the checks will largely save them. I’m not a big fan of Ricardian equivalence, but giving people who aren’t cash-constrained checks they know are one-time is as likely to have a near-zero effect as any policy I can think of. (And the portion of the checks going to people who really do need them is income support, so the previous argument applies.)

Pandemic control, however, is clearly expansionary fiscal policy, just like defense spending, and may have a reasonably high multiplier. So shots in arms and virus-proofing schools, plus a bit of check-fueled consumer spending, is what might overheat the economy.

The question then becomes whether it will be too much stimulus for the Fed to control any inflation surge.

It would be silly to pretend that we have any certainty about what’s going to happen. If I had to make a best guess, however, it would be that we’re looking at a true stimulus of around 3 percent of GDP. If you want a historical parallel, this is in the same ballpark as Reagan’s fiscal expansion via tax cuts and increased defense spending — an expansion that did lead to relatively high real interest rates, a strong dollar, and a wider trade deficit, but did not lead to a resurgence of inflation.

This guess will almost certainly be way off, one way or the other. But here we come to the asymmetry of risks. If the economy is weaker than I expect, it’s not at all clear how the Fed can offset it; if it’s stronger, tighter monetary policy will be easy.

So putting it all together, it makes perfect sense for a Covid rescue package to be substantially bigger than the “output gap” as conventionally measured. Such a package will probably deliver significant net stimulus, even though that’s what it’s not about. But it doesn’t seem likely to produce more inflationary pressure than the Fed can handle.

The stimulus payments are one-time payments, not continuing payments. Even if their effect is inflationary the effect is unlikely to persist beyond a couple of quarters. Once everyone has spent their stimulus money their spending will decline back to baseline and the inflationary pressure evaporates.

I'd be curious to learn more about what these public health and education portions are buying. In other words, would vaccination be slower and schools reopen slower without this spending? Doesn't seem like there is much discussion of that.